| sinking feeling | ||||||||||

I Was a Swim Pal in Abruzzo!

by Gregg Williard

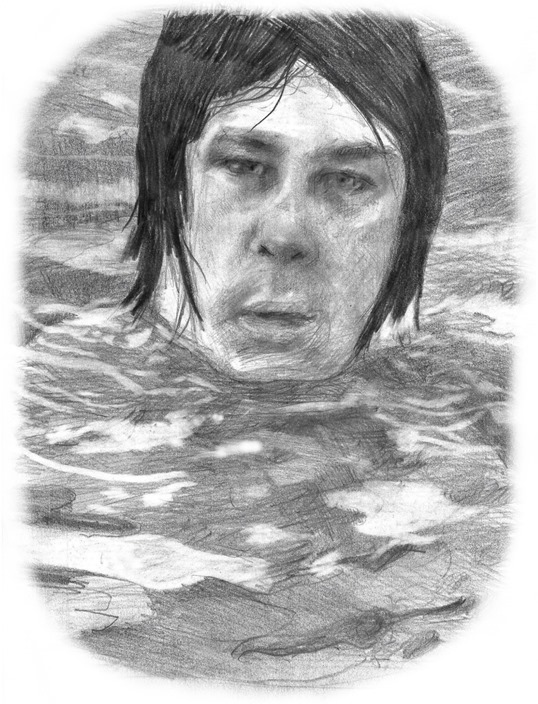

Dominic said I looked like someone who was comfortable in the water. I told him I could barely swim. Dom said, “but you can swim, right?” He told me he knew it, because I was born for an amazing job: “How would you like to spend the summer as a swim pal in Abruzzo, Italy?!” He celebrated my regular features and broad shoulders. If I let him peroxide my hair silver blond and take me to a tanning salon, well! My blue eyes would be irresistible against lightly browned skin! But what if someone is drowning? He yelled, no problem! A swim pal in Abruzzo works only in the shallow end of the pool! But, I countered, I’ve heard of people drowning in two inches of water, but Dom explained that’s only if they want to die, and believe me, the pals of the swim pals of Abruzzo are kids of wealthy tourists, and they do not want to die! I wasn’t so sure about this, but he said the job paid very well and was ridiculously simple: put on a pair of trunks and a tee-shirt, (the guests at the resort are very conservative and modest), and do laps or something like laps, or just walk around and splash in the shallow end until one of the tourists, or their kids, select you for an hour of companionship in the pool! “Don’t worry! You will be selected!”

“What is it they do, exactly?”

“They pal around!” The pals all had a clear waterproof plastic pouch belt worn at all times in and out of the pool. It had a pen inside and a printed form (called by management, “Lessons”). You signed your name, the start and finish times, and a signature from the parent of your client. They recorded your time in a ledger and paid you for your time at the end of the week. Very simple. The swim pal staff was housed in segregated rooms of the old hotel. He brought me a sample plastic belt pouch with a copy of the form and a ballpoint pen. “See? A real Bic clear stick! The kind you like!” This was how we first met at the student union. I was studying with a couple of other students and was extolling the virtues of the Bic clear stick, which seemed to be harder and harder to find. Bender, another student with a rash on his neck he said he got from the salad dressing at the cafeteria, added with a bitter expression, “Yeah, the bookstore is all ‘gel this and gel that!’ Fuck those gel pens!”

“Yeah!” a large girl named Cindy said, “Fuck those gel pens!”

Dom was crying now, and said he needed my help. “I’m sorry Dom, but I have continuing doubts about being in the water…

He pulled me to one of the dorm’s rickety knock-off Eames chairs. “Let me tell you a story. There was a rich descendent of the Marquis Gilbert, a French aristocratic family with a villa in Abruzzo. I met the lad while working as a swim pal. The boy was my assigned pal, you see. In Abruzzo. Everything was going, as they say, swimmingly.” Dom’s lapse into mannered, ponderous diction should have been funny.

“The boy, whose name I can’t seem to recall,” (what?) “got an ear infection from the pool that worsened into deafness. The family Gilbert were uncommonly sympathetic to my anguish, and never blamed me for the misfortune. As the boy’s white hands fluttered around us with sign language, almost like a flock of doves taking flight, the Gilberts wanted only one thing: that I return to Villa d’Abruzzo once a year to host a special gala in honor of the boy…”

“Hence your devotion to the swim pal program.” He ignored this and went on.

“Little did I understand that the ‘gala event’ would be a nightmare of dismal humiliations!” Dom explained that the Villa d’Abruzzo was really a broken-down dump and the guests “pasta trash” from a nearby trailer court that the deaf boy signed as “the court of the Duca d’Puke.’ The worst of the guests were a progressive, Montessori-Maoist daycare collective. The Gilberts gave over a salon to them and their hoard of small children, whose supervision was Dom’s special charge. Part of the group’s revolutionary pedagogy was an imperative to never change their diapers. “Yes,” Dom said, anticipating my question. “You heard me right! A whole classroom of kids with shit in their pants! And I had to take care of them!” At this his face scrunched up into such abject misery that I was transfixed. I knew that I had no choice. “Where is that tanning salon?”

“Please don’t go, buddy. I’ll tell you the truth. The boy didn’t just go deaf. He disappeared, and the Giberts are sure he’s dead. That’s why I need you, buddy! I’m telling you, with bronze skin and bleach-blond hair, you’re a dead ringer for the boy!”

“All this, and you still can’t remember his name?!”

“It’s coming to me! It’s coming to me!”

One of the sleepy undergrads groaned, “Shit, man, this is a study room. Can’t you keep it down?”

I lead him out of the room and outside to the bike racks. Dom started telling me more in a rushed voice. Maybe I could fool the Gilberts into thinking I was the lost boy! (But wasn’t I too old? How much time had elapsed since he disappeared? Wasn’t he deaf when he wandered away? How would I pull that part off? I didn’t know sign language and was hardly going to devote time and energy to learning sign language, not to mention Italian! Or was it French?) It was absurd, but his confidence in the insane was unerring. He could tell the Gilberts (Dom pronounced the name with a ludicrously exaggerated French accent: hard G like Geese-GEE-BEAR that set my teeth on edge), that the boy (but what was his FUCKING NAME?!) had suffered a memory loss and the trauma of encountering his family too soon might be an irreparable shock. He would let them have a glance at the boy (me) from a distance, where the age difference could be disguised by my crouching down low in a car, with the boy’s favorite hat pulled low. As the story rushed by, I searched the bike rack, but my bike was gone. Then I saw it across the street, with the Kryptonite U-lock hooked to a lamp post. “C’mon!” I crossed the street and inserted my key into the lock, but it wouldn’t open. Of course, they had broken my lock and put on a new one. Dom said, “Are you sure this is yours?”

I pushed by to find the thief. He called me back and took hold of the U-Lock, twisting it with a sudden odd move that made my head swim. With a clunk it was free of the lamppost yet still locked shut. “What did you do?”

He motioned for me to get on the bike. “I learned it in Abruzzo.”

I rode away slow, woozy from Dom’s trick with the lock, veering down an unfamiliar side street of old store fronts: a Chinese laundry piled with brown paper bundles wrapped in string; a bank branch the size of a closet with a dead screen ATM; a shuttered office with BUSINESS across the glass. I peered in and saw desks, blotters, rolodexes, goose-necked metal lamps, staplers, rotary phones in a uniform olive green, gray and tan. The way military things used to look. I liked the look. Not necessarily the olive green, just the uniformity. Gray or brown was ok. I hated, still hate patterns in things. But always find theme patterns, language patterns in things. So, dreams. This office a good example. There was even a sun-bleached slide rule. It looked like my father’s old office. Since I was a boy my father always asked me to tell him my dreams from the night before. He didn’t interpret them. In all other ways he was perfectly ordinary. In the hospital near the end he asked me again. I should have told him something.

“You wanted to book a flight to Rome? It’s very expensive there.”

“I’m going on to Abruzzo, Dad.”

“That’s just great Gregg!”

I wanted to ask him where he had gone, what had happened, what was happening at that moment. Instead I explained irrelevances, inanities. The only things that would stay still for language. Was this all I could tell him? That I was going to work at a pool for the summer? My father rubbed my shoulder. “You’re looking good! You’ve been getting a lot of sun, your hair is bleached almost white, and your skin is dark as a mulatto!” I winced, reminding myself that he was from another era. He asked me for patience to find the right forms to make the reservations to Rome, and Abruzzo. I urged him not to go away again but he disappeared into the back of the office. I waited at the desk for a long time, rereading the backwards BUSINESS across the storefront glass. I recalled Dom’s story of the Family Gilbert (GEE-BEAR), and the small white hands of the disappeared, nameless deaf scion, signing in a flutter around them “like a flock of doves.” Mike’s wife was deaf. He had met her acting in the play, Children of a Lesser God. I waited. Outside the window dusk settled. I went back to the dark interior of the office. My father wasn’t there. Unnerving detail. Maybe my memory of his last moments is flawed. His eyes were closed and he was smiling. He was gone. I never knew why he wanted me to tell him my dreams, but perhaps he knew that when we were able to see each other again, that’s where it would be.

I got my bike but didn’t ride back to the dorm. I needed to follow up on a therapist referral that I had gotten from the student counseling office. I went to the mental health center and told them my name. They looked up my records and sent me to another floor, where psychotics wandered the floor and the nurse’s station was empty. It was a scary place and I didn’t want to stay. They said my doctor would be with me shortly. I sat in the waiting area and fell into a reverie about Abruzzo when I saw Dom down the hall talking with one of the nurses. I got up and left, taking the wrong elevator and ending up in a dark subbasement. Was Dom a patient, a mental health worker, or, (as I was beginning to suspect with Dom) a duplicitous fusion of the two? Damn that Dom! It seemed like everything familiar and comforting about my student life had been turned upside-down. That night in the dorm my sleep was full of nightmares. The worst had me taking care of a cat in a bag, until I inexplicably stabbed it with a fork. As it mewed and bled I told myself it must have had a fatal disease and I was just putting it out of its misery. But was this true? The next day after classes I contacted the clinic and apologized for missing the appointment. I was able to reschedule, and in the session I told the therapist about the dream. He said that he hoped next session I would let the cat out of the bag and maybe heal the wound. I wanted to tell him about Dom but we ran out of time.

I returned to my dorm room. My roommate Stanley said Dom had been asking for me. He said, “I don’t trust that guy. He acts like he’s some big deal, money or family or some shit. Notice how he never gets specific about anything. I don’t give a shit. I don’t like the way he goes around making offers, promises, acting like he knows everything.” I told him I agreed. “Then what are you doing getting mixed up with him?” I sat on his bed while he opened a bag of chips that we finished in seconds. He looked at me with concern. “He didn’t offer you some kind of job in Abruzzo, Italy, did he?”

“Yeah.”

“Don’t tell me. A ‘swim pal’ for some deaf kid.” He tapped his hair, which was bleach blond just like mine. “A swim pal for a deaf kid. That’s rich. I was going to be a gardener for a rich blind girl in Abruzzo!”

“A gardener?”

“The pay was perfect. I didn’t need to know anything about gardening. Good thing, ‘cause I don’t.” Looking at Stanley’s bleached hair I suddenly realized that most of the students on our floor had the same bleach-blond hair and tawny skin. I thought it was a fashion. I was slowly catching on to the far reach of Dom’s strange charisma. Stanley crushed the bag in his fist. Some chips were still inside and I regretted the waste. “And since the rich girl was blind, I could tell her anything at all about the wonderful flowers I was growing in her garden, even if there was nothing but weeds or dirt. I could go on and on about the succulents and orchids, the colors and rare varieties so prized in the valley of Abruzzo.”

“But what if she wanted to touch them? Smell their fragrance?”

“I asked that very question. Dom told me no problem. He would always be silently by my side with a few real flowers and a selection of rare perfumes to sprinkle on the samples, creating the illusion for the blind girl of a ‘vast and rare array of growing things.’” Stanley tossed the bag in the trash can and missed. “’A vast and rare array’!” he hissed bitterly, rubbing his hair as if to wipe it free of bleach. “If I see that fucker again, I’ll kill him!”

I tried to calm Stanley but it gave me a headache. I left to find another place to study for the evening, drifting back to the piano bar student lounge I found it empty and settled into my favorite study carrel, hidden behind a potted plant that wasn’t real.

The topology homework was hopeless. I had chosen it as an elective, with a faint hope that learning about topology would help me become mathematically literate, smart in some expansive transformation from schlemiel to scholar. It was astounding how these aspirations outstripped any real understanding. I had expressed this frustration to Stanley, and he told me a story about Robert F. Kennedy Jr. “Bobby said that he was always at the bottom of his class for years. Then he started doing heroin, and suddenly he could sit still and read and was acing every class he was in.”

“What, are you saying I should do heroin?”

Stanley had opened another bag of chips, or maybe Doritos. He did not offer to share. He chomped and berated, peppering the bed with polygons of Dorito crumbs, recalling the topology work sheet and questions I could not make any sense of:

If you prefer Figure 13 (a) showing the torus with the four glued vertices becoming one, and the four edges become two loops on the torus, then will Figure 13 (b) only appear as a finished or unfinished DIY job?

I buried the memory in my notebook, along with endless tries and scratching-outs of notes on the topology questions. None of them lead to anything. Then I heard Dom’s distinctive, grating purr of a voice. He entered the lounge with his usual retinue of freshmen, regaling them with some story of his family in Abruzzo: “…and my father always told me, ‘I come from the generation when a hat rack in the corner stood for something!’” The loudest laughs came from a small guy with bleach blond hair and tawny skin. I stooped behind the plant that could not die.

It will be unfinished. But the single surface obtained from gluing the triangle, the pentagon and the square in Figure 14, following all the gluing directions a, b, c, …f on the surface. How many vertices will we ultimately have?

“’Stand for something!’ A hat rack in corner!” The blond kid was doubled over with laughter, and I was hoping Dom would be distracted and not see me. But he did and hurried over to the carrel to greet me as if we hadn’t seen each other for weeks. He pulled up a chair and leaned in close. “God, I’m so glad I caught up with you!”

“Dom, I’ve got to finish this homework for tomorrow.”

He didn’t seem to see it at all but said, “Oh that intro to topology is nothing. I’ll help you make sense of it in no time.”

“Dom…”

“Listen, there’s going to be a very, very important event in Abruzzo coming up! If I book your flight right away…!”

“Dom, I’m not going to Abruzzo!”

He didn’t seem to hear me. “It’s a party, and your presence is absolutely essential. Now, don’t reject this out of hand, but you will have to wear a very expensive wedding dress—white, with a shawl and…but don’t take my word for it.” He gave me folded paper.

It was a handwritten note in the dark thick ink of a fountain pen. “What is this?”

“It’s from your old friend Will Reeves.”

“What?” I hadn’t seen Will in sixty years:

I hope this finds you well. I’m writing for my friend Dom, who needs your help! There’s a big party day coming! The celebration requires that you wear a wedding dress with a shawl. As you prepare for the party, you will scurry around the house, straightening books that are all inexplicably black! Even the pages! You will adjust the rabbit-ear antennae on the TV, hesitate between The Game and Old Horror SF! Choose carefully!”

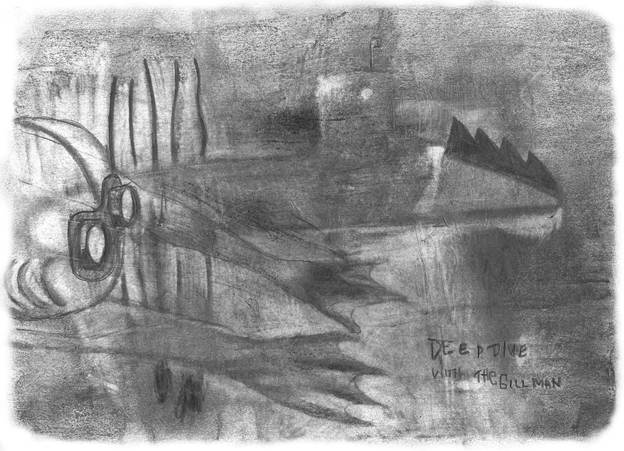

Will had done meticulous tiny ink drawings of airplanes. He had always praised mine, done in the cafeteria of our school where I spent the happiest days of my childhood. I realized I had just published a short story about WWII fighter planes. I thought of the older Hemingway, getting off a plane in a drug and alcohol stupor, trying to walk into the spinning propeller. I gave the letter back and scooped up my books to shoulder my way through the crowd of blond and tawny-skinned students, like the effete Eloi in the George Pal Time Machine, or the alien children in Village of the Damned.

I had to find a different study space! And maybe I should answer Will’s letter, if it was real. But how was Will an “old friend” of Dom’s? It was more lies. I didn’t even want to know how it was possible. I escaped Don and his entourage and wandered the streets. I passed an unfamiliar empty storefront, (like so many others in the neighborhood). But this one had an odd sign in the corner, a reproduction of the old title logo of the lurid Mexican tabloid Alarma:

What kind of store was this? It was The Alarma Bar and Grill! Inside were many foreign students. A refugee bar! I joined a round table of customers. It was covered with glasses of beer and pretzel crumbs. The mood at the table was incoherent: jolly laughter, tears, angry arguments, vacant, trauma eyes. Lots of languages. One guy wanted to pick a fight with me, but another was friendly and pushed him away to offer me a beer. I said I didn’t drink but thanked him. He pointed to the TV over the bar and said, “You must know this one.”

“As a matter of fact, I do.” It was an old black and white movie, a low budget SF-horror adventure from the late 1950’s titled The Atomic Submarine. It was too noisy to hear the dialog or music, which was a shame. I was lost in the film, and the friendly guy looked lost, too. He was a 50ish Caucasian with a neatly trimmed salt and pepper beard but with a faint Asian cast to his features, like American actors that have lived for years in Japan and appeared in Godzilla movies to represent stock Gaijin characters (usually generals or U.N. officials). I asked him if he spoke Japanese. The friendly customer nudged me out of my reverie and said something weird was going on down the bar: a menacing gang taking over seats, giving out little papers with blurry black and white images of torture, or porn. Printed on them were QR codes we were ordered to rub with our thumbs. The link was subdermal. Link to what? I wondered. I got up to go to the bathroom, which was down a narrow hall. Something about this ordinary, endlessly repeated ritual – (getting up in restaurants or bars, going to public bathrooms, surveying their bland or bleak architecture, their light and scent) – hit me as an extraordinary threat, or gift, a secret site of wild gods and black matter mysteries.

I fled the bathroom, fled the restaurant, throwing out the subdermal link and hoping none of it had penetrated my skin. Immediately a friendly, familiar face accosted me for keeping him waiting. “C’mon, were going to Abruzo!” Dom led me to a car nearby and a woman who filled me with the same familiar warmth, yet I could not remember who she was. She leaned over the front seat and chortled, “Jesus, you’re so slow! I thought you were never coming!” Jesus. Never Coming. Then coming. A joke, a double-entendre, amplified by the smokey voice and round, sensual face and body, like a sexy Dutch resistance fighter machine-gunning nazis. I tried to ignore her by focusing on the passing lit windows, glimpsing shadows of people, the edges of chairs and doors, and the flashing dance of big screen TV’s doing edits that lost all sense beyond those rooms. In the dark between windows I saw black ink, the up-close cross hatching I had stared at all day working to finish a drawing that was almost more white-out corrections than ink. The white tack still smelled and my fingers still sticky. I took a sniff and heard at the same moment from the front seat a growly voice in French, coming through a tinny cell-phone speaker tuned to an old movie, with strings and a moaning chorus rising behind it. The Dutch-looking woman was lit white and rapt before her phone. I asked her what it was and she said Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast. I recognized the scene: La Bete’s smoking magic glove that transports La Belle between realms, taking me to remembrance of the “Demon with a Glass Hand” episode of The Outer Limits, with the secret of humanity’s disappearance (all of humanity recorded onto a wire filament in the hand). Beyond the lit windows ink on ink. The wisdom of the octopus jet of black ink, the rightness of it, even if lost inside the cloud. The friendly woman turned and said we are supposed to be going to the office to get rid of the DEI words, but we really putting them all on a wire filament, until the time when we come back, and rid the world of the invaders, forever. Dom was radiant with happy conviction. “Now we’re really going, you’re really on a mission, you’re really going to live! Next stop ABRUZZO!”

“Dom…” It was all impossible. I was going to drown, or be trapped with Marxist Montessorians, or worse. But I just didn’t have the heart, or the will, to say no.

![]()

Rate this story.

Copyright is reserved by the author. Please do not reproduce any part of this article without consent.