| Maxwell's Page Four | ||||||||||

![]()

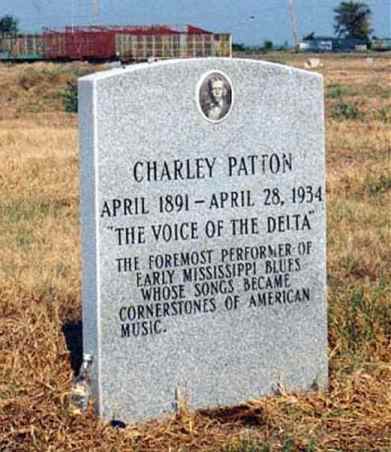

Sonny Clark. Sonny's Crib (Blue Note Connoisseur Series)

Donald Byrd-trumpet

Curtis Fuller-trombone

John Coltrane-tenor saxophone

Sonny Clark- Piano

Paul Chambers-bass

Art Taylor-drums

In 1963 a thirty one year old Sonny Clark died way too early, another victim of club-land lifestyle and his own appetite for various poisons. Although around for only a brief time, he managed to contribute to some seminal Blue Note sessions both under his own name and as a sideman.

His was the rare case of coming onto the scene fully formed. There was no evolution of style over the years into what would become his own distinctive voice. Sonny was part of the second great wave of pianists to emerge in the late fifties (Wynton Kelly, Bill Evans,et al). He shows his influences, mostly Monk and Horace Silver, the percussiveness of Bud Powell, but in his hands these are the foundation, the building blocks. A way to steer towards his own explorations. Even when the influences bubble to the surface, his is a divergent path. His percussive runs seem more melodic than Monk or Bud Powell. When backing another player's solos, whereas Horace Silver often opts for a gospel-dance style comping Sonny goes for a more single note fluidity during these moments. Yet Sonny's willingness to allow glimpses of influence to peek through make his own playing all the more compelling, his solos statements an artistic logic unto themselves.

During his brief career his style and tone did not change. Whether this was a fidelity to a specific artistic vision or the lack of time allowed for any type of evolution will remain unknown. He played with a clear ringing tone, often percussive but

never overly showy or distractingly busy. His was a mix of West Coast cool-sophistication which allowed for wider range of colorations in his compositions and arrangements similar to fellow luminaries Sonny Criss and Charles Mingus of the Central Ave (LA) scene. The West coast cool mixed with some east coast aggression in his compositions and playing to make for some forward thinking hard-bop writing and performing in tandem to what Clifford Brown, J.J Johnson and Jackie McLean were doing. Mere bop formula being abandoned to create pieces of greater complexities, which did not rely on mere showmanship of the solos.

Sonny Clark got his start backing clarinetist Buddy DeFranco. At a very young age he was sent on European tour, doing a large multi- act tour that was the derigeur for any jazz group(s) with ambition to not be confined to simply serving residency at

one of either coasts then thriving jazz club scenes. Then too, there was the added appeal of being given the respect deserving of true artist, an attitude often lacking in the then still segregated states. He was given a brief solo spot (doing a version of Somewhere Over the Rainbow before it became an overly maudlin show piece for other artists). He was the youngest player on the tour but still managed to be one of the most compelling pianists, showing some influences but never falling into the simply "sounds like" way of playing.

In 1957 after serving a one year residency at the famous West coast answer to Birdland The Lighthouse he came east. He was heard in clubs and picked up by Blue Note's Alfred Lion. His first album, (1957) Dial S for Sonny.

Sonny appeared on more albums under others names than ones featuring him as a leader. Under his own name only half were released in his life time (3 of 6). Regardless of whose name is featured first, his voice is prevalent on all these great and diverse recordings. His most famous association being featured as part of an informal Blue Note house band with Butch Warren on bass, Billy Higgins on drums, which was featured on Dexter Gordon's albums Go and A Swinging affair. These were the two albums Dexter cut right before his fifteen year self imposed European exile, Go being said to have been his all time favorite. Until his return, Dexter would continue to record for Blue Note but using fellow American in Exile pianists such as Bud Powell and Kenny Drew. For aficionados though, there would never be as much chemistry or sympathy as what he had received from Sonny's support. The trio would go on from the Dexter recording sessions, showing up a few weeks later on Jackie McLean's Blue Note date A Fickle Sonance. Sonny then used this band for the Blue Note done as leader Leapin and Lopin. There was also another partnership which bore fruit, shelved by Blue Note for decades, between Sonny and guitarist Grant Green. (see The Complete Quartets with Grant Green only recently released)

What makes for a masterpiece? This album was recorded two weeks before John Coltrane's only Blue Note date as a leader, Blue Train. It features same type of three horn line up ( trumpet, tenor sax and trombone) and actually shares some of same musicians (Curtis Fuller and Paul Chambers). This aside the albums are vastly different, although both are worthy of continuing to garner devotes. For me, Coltrane has always placed in my personal top three jazz pantheon, but title track aside, I prefer Sonny's album more.

It is a combination of naturally flowing interplay between all the musicians and great material for them to draw from.

The cast here is 'stacked' but unlike some other albums from this time full of heavy hitters, they do not rely on an albums worth of mere blowing blues based numbers.

This album finds John Coltrane right in the middle of his sheets of sound period. He had just finished serving time in Miles band of 1955-1956 which did a marathon recording session of four albums for Prestige/Fantasy (Steamin, Workin, Cookin and Relaxin). It was from this initial tutorship under Miles and his own inherent genius his playing and vision would grow more expansive. This album and the Miles at Newport-58 (Columbia) perhaps best show the emerging of John Coltrane's lighting in a bottle

which was not fully understood or appreciated by everyone right away. It would be two years hence that he would participate in bringing to the fore modal jazz with the Rosetta stone of jazz, Kind Of Blue (Columbia). This is one of his very last straight out hard-bop dates. The blues would always figure to some extent in later works but never again so straight ahead. His tone and playing sound fresh and excited which was not the case on every cut on certain earlier albums where his vision was in flux.

In the early sixties Donald Byrd shined on Blue Note. It did not matter whose date it was, his playing was always a thing to be enjoyed. His tone is bright and his playing has a percussive sharpness which recalls Clifford Brown and the splatter school, although containing none of the occasional rawness which could sometimes show through. Like Sonny Clark he would make some incendiary Blue Notes with Jackie McLean.

Curtis Fuller directly follows in J.J Johnson's footsteps. Before J.J Johnson a trombone in jazz was allowed to wah-wah or slur, filling in a band's sonic holes. J.J Johnson was first musician to play his trombone the way Bird did the alto sax. He opened up a world of possibilities for both bands and musicians. He was often referred to as bop's intellectual, for his forward thinking song structure construction and insight and his own personal playing. Curtis Fuller continuing in this vein would appear again with John Coltrane a few week's later on Blue Train. His playing fitting in nicely with the hard-bop idiom but never succumbing to creating a specific formula in song or solo as sometimes happened in the earlier eras straight ahead bop music.

Paul Chambers would appear alongside John Coltrane many more times in various bands of Miles Davis and also on many more Blue Note albums. His style playing was always perfect for the time he spent walking among giants. Always even, always where you

need it to be. Art Taylor also had been on many Blue Notes. While not as 'famous' as some of the other drummers these players switched between, I think that works greatly to this album's advantage. There is none of that 'look at me' thunder burst that can occasionally pop up in a song and distract.

The CD is remastered and comes with two bonus track, which are alternate takes standing strong on their own. There are no weak or dead tracks to be found on this album, something which can not always be said even of the best jazz albums. The sound is very good throughout. My only bone of contention is, it would have been nice to have along with the original liner notes 'Another look at' which are new liner notes always included on the Blue Note Rudy Van Gelder remastered reissues (RVG). The connoisseur series is a limited edition deal and cost more than the RVG editions, so one would think it is the least they could do.

While there are no weak tracks, my personal favorites are the standard Come Rain or Come Shine. It is slow, romantic lament. I have found it is often harder for a good musician to play slow and soft. For what ever reason the songs may contain tiny moments of beauty but often sound like what the band would play while one member is having a smoke or the audience orders more drinks. Not here though. John Coltrane's solo contains a melancholy regret which verges on becoming tangible poetry. Donald Byrd's solo entrance maintains this tension. His tone throughout conjuring up lyrical fragility very few trumpeters were capable of bringing fourth.

There is also a fantastic cover of German composer Kurt Weil's Speak Low. It is given a Latin tinge but still manages to convey Kurt Weil's original intention, a celebration of longing. Curtis Fuller makes a fully realized bop-like statement in his solo while Donald Byrd's playing remains bright and clean but is shown in a more aggressive light.

Like a lot of the gifted artist of his time, Sonny was troubled and gifted. What remains of the man, his artistic legacy is well worth exploring.

-Maxwell Chandler-

December 2005

![]()

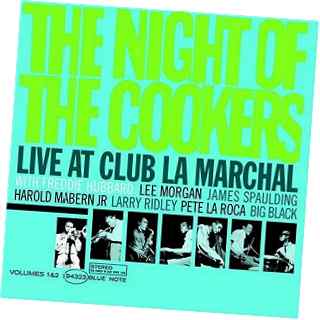

Freddie Hubbard, The Night of the Cookers (Blue Note Records)

Freddie Hubbard-trumpet

Lee Morgan-trumpet

James Spaulding-alto sax/flute

Harold Mabern-piano

Larry Ridley-bass

Pete La Roca-drums

Big Black-congas

Freddie Hubbard was part of the talented post bop wave often (then) referred to as 'The Young Lions'. Unlike the generation of greats before them, they were not all of one 'school' and many would continue to evolve through the ensuing decades.

The emergence of Blue Note Records as a true power in the jazz world also had a part in shaping the musical community of this time. Blue Note's policy of paid rehearsals allowed for their artists to concentrate more on original compositions of greater complexity. The emerging technology also worked in their favor. The long playing discs were now standard (for all labels), allowing musicians/composers to fully realize their artistic ideas. In this climate of exploration and collaboration would be introduced inflections of modernist chamber music-like pieces and world music flavorings. This was Blue Note and their stable of artist in the late 50's / early 60's. The close of the decade would see further explorations with ( in some opinions) artist going electric and loosing their way. Or, becoming too bogged down in commercial considerations.

Freddie Hubbard has a jazz pedigree which is truly impressive. Where and who he has appeared with, this sizeable body of work, includes many albums which would be on the aficionado's top ten list.

He got his start with one of trombonist J.J Johnson's groups. He was also seen early on with Dexter Gordon, in Dexter's first Blue Note album 'Doin' Alright?. His most steady home initially was on the front line of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. Many of the people Freddie worked with early on had also been in Art Blakey's band, a sort of jazz college they all attended, just not necessarily at the same time.

Another inherent strength of both Blue Note and, in general the jazz world at this time was a steady stable of artists who appeared on each other's albums creating an artistic familiarity greatly to everyone's advantage. There was an almost tangible connection among these artists inspiring and borrowing from each other over the course of cross connecting informal partnerships. During this period Freddie Hubbard was part of the holy trinity of trumpet greats (Lee Morgan and Donald Byrd sharing this generation's Mount Rushmore).

Personally, the appeal of Freddie Hubbard lay not only in his chops and tone, but his compositions too. While his peers would occasionally venture into extended forward thinking pieces, (Donald Byrd A New Perspective, Lee Morgan Search For the New Land, Hank Mobley Thinking Of Home) his album often feature multi-horn front lines playing harmonically complex pieces which combine sophistication with emotion.

His debut album Breaking Point (Blue Note Records) was the first made after leaving the Jazz Messengers and introduced the important partnership he would have with flautist/alto sax player James Spaulding. Freddie would go on to incorporate even larger instrumental lineups into his compositions and recordings often including James.

During this time, there was a never accurately named jazz emerging from musicians who had far transcended being just entertainers. It was traditional jazz instruments now often combining with less obvious ones. They were playing music which merged their roots of jazz and blues with something new, a modern chamber type sound far different from the once novel third stream marriage of classical and jazz. This music also embraced some of the discordance of the free-jazz movement and some of the harmonically complex ideas which had been the cornerstone of Europe's 20th century classical composers. All the while maintaining the exciting air of improvisation, one of jazz's key ingredients.

Through no fluke, Freddie appeared on a lot of these albums, enriching them with his own take on this complex, heady amalgam. Both Freddie's writing and playing really seemed to shine on larger ensemble pieces. John Coltrane's Ole (1961), perhaps one of jazz's most epic statements, included him. Ole was a rarer large ensemble effort for John Coltrane, containing his core 'classic quartet' and also making use of multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy and added bassist Art Davis. Soon after, Eric Dolphy would recruit Freddie to play on his own classic 'Out to Lunch' along with Bobby Hutcherson who would also incorporate Freddie into his band for his first album as leader 'Dialogue'.

Aside from James Spaulding another important musical connection was made with Herbie Hancock. The 1964 debt album as a leader by Herbie, Empyrean Isles featured a saxless group, with Freddie achieving a richer sound by substituting on cornet. The rest of the group was what would become core ingredients in Miles Davis's immortal free-bop group. The follow up album Maiden Voyage had the immediate precursor to Miles Davis's free-bop group including Wayne Shorter's predecessor and short lived member of the band George Coleman on tenor sax.

In the late 1970's the full free-bop group with Freddie in place of Miles would tour under the banner of VSOP. All the members of the band had been voted best at their instrument which is what birthed the name. They would release two live albums: 'VSOP The Quintet Live' and the only recently available 'VSOP Live Under The Sky'. The later of which is said to be one of if not the first direct digital live recording. It was recorded at the Denen Coliseum in Tokyo and the energy of the 10,000 fans who braved the rain is palatable.

Unlike some of his peers Freddie Hubbard was not better or worse when comparing studio to live performances. He always seems to intuitively know the best approach for the situation.

The Night Of The Cookers is a two CD RVG edition Blue Note. Originally it was released as two separate records, using the same graphic, just in different color for each record. For their multi record live recordings Blue Note always did this, although Freddie's record was the last to use this packaging after which the marketing department wanted something to better pull in the youth-rock market. Even though it is a live recording the sound quality is excellent. Each CD has only two songs on it, but each song averages about twenty minutes. It includes the original liner notes and also 'A new look at' notes which examines the artist and album through the hindsight of history.

The perfect bookend to this set is Freddie Hubbard's Blue Spirits. Blue Spirits was recorded only two months before this album. It was made up of three sessions which included changing four horn front lines and three different pianists (separately).

The songs on this album are complex and what could be considered Freddie's core group here would be found again on Night of The Cookers with the addition of Lee Morgan. Some of the same songs are presented on both albums with different feel but to great effect. Blue Spirit presents an overall darkness, not the type which could signify an end. It is more an urban darkness, where beauty and desolation meet. Hearing the same piece from both settings also allows a fuller appreciation of how perfectly Freddie was able to marry song structure conception with what he wanted to say in his own solos.

Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard had both been in art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, usually at different times. Two years before this recording they had worked together in Jazz Messengers for the Broadway musical Golden Boy for Colpix and also on the Limelight album Soul finger. While not bad, neither truly allowed them the opportunity to combine complexity with cutting loose.

What is immediately apparent with Night of the Cookers is that despite being a live recording containing two titans, it is not mere blowing contest. Through out the two CDs the entire band sets up long soulful grooves in lieu of filling in space while waiting their turn to solo. Truly, it is the interplay among the musicians that make this one of the most compelling documents of a live band in full flight.

Some stand out moments for me include 'Walkin' which includes a James Spaulding solo playing over the locked groove of drums and conga. His tone here transcend hard-bop and verges on the free. Within his solo statement James Spaulding manages a musical alto summation of all that had happened, from Bird's bop to Eric Dolphy's free-new thing. On some songs James Spaulding does switch between alto and flute which I have never been a big fan of, but the flute is far more a flavoring than a feature.

Breaking Point sounds like a joyous Latin tinged revival meeting. The piano sets up a pattern which creates a rolling tension for all the others to call out over.

Within this recording too, is one of the rare times Lee Morgan tries his hand at mute horn playing, achieving a warm vibrato hum effect similar to piccolo trumpet sound.

Over all there are no weak links in this band, no moments to disrupt the tension and joy. All these artists had worked together over the years and they all wanted to achieve the same thing with their art, which clearly shows here.

There is a lot of debate about Freddie Hubbard's post Blue Note years. Too often if a great artist later stumbles, it seemingly detracts from what initially made their reputation. To some extent art is subjective anyways, but no matter what a great artist goes onto do, the initial greatness should not be forgotten. It is this we should treasure, it is this which lasts.

-Maxwell Chandler- Jan '06

![]()

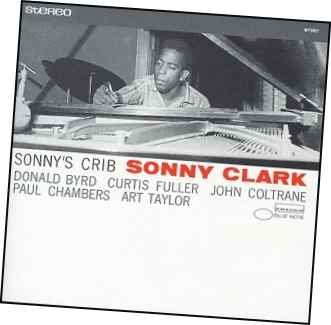

Charley Patton, The Definitive (Catfish Records)

Charley Patton-guitar/vocals

On some tracks:

Willie Brown-second guitar

Henry Sims-violin

Bertha Lee-vocals

The late 1800’s/early 1900’s, the term “redneck” had drastically different connotation than that which it carries today. Initially it was a verbal short hand to describe the Irish and Scottish immigrant farmers down south. After a day in the fields their necks burnt a lobster red. Like all who joined the great melting pot with dreams and hopes of something better, they brought their songs to sing with them. Folk melodies, murder ballads, played with a lot of the instruments which would be used for the early country music. This mixed with the sung laments of plantation slaves birthed the blues.

The earliest blues was a complex amalgam of these three seemingly divergent sources, country, folk and plain song brought over by the slaves. In the far future practitioners may have more chops, but the construction and influences would never again be as open minded, nor as organically mixed.

The embodiment of this first great wave of bluesmen was Charlie Patton. The exact date of his birth is often debated. Given sometimes as April 1887 or 1891. He himself was never sure, the later date being supplied by his parents for a 1900 census poll. He could not read or write except his name which he always slowly spelled out loud C-h-a-r-l-i-e. Ironically throughout his oeuvre it is spelled Charley.

Charlie was descended of mixed blood which included white, Native American and African American. The oddly pejorative term “good hair” (Caucasian-like) was often used to describe him when not talking about his music.

His family was religious and disapproved of his music and his casual teachers. The music was referred to as “Devil’s music” and his romance with it often earned him beatings from his father. Eventually, for whatever reason his father eased up, even buying Charlie a guitar. It was shortly after this he hit the road never again to return home for any real length of time.

Charlie’s main recorded output was the blues, but this was far more a financial decision on the part of the record company than a personal artistic choice on Charlie’s part. It was the same commercial consideration which largely kept Charlie’s less blues like pieces from ever seeing wax.

He did not seem to mind. Often to give an audience their money’s worth, when performing Charlie would toss and catch his guitar, play the underside percussively, drum like or when the mood struck him, behind his head. Considering what was resonating from him, all far from necessary.

Although he never liked to complain, like many artists of his day (and sadly, in ensuing decades) Charlie was taken advantage of by record companies. He and other artists would have to commute to Northern cities to record or in makeshift studios set up in barns or flop houses.

These early bluesmen were pursued by record companies not out respect for their artistic merits but in hope of creating an African American record buying (phonographs too) public. With few exceptions this was driving vision behind these small companies.

Pony Blues was successful, Charlie’s biggest seller (Paramount Records). In keeping with the times only the smallest trickle of money went to him. From his point of view, while never becoming rich, he was kept in sandwiches, whiskey and smokes. Always happy enough to not have to do manual labor as often.

Pea Vine Blues used a new gimmick thought up by the record company. The record was released with a contest. The singer was listed as “The Masked Marvel” its cover depicting an illustration which looked like Charlie donning a Lone Ranger styled mask. Contestants were asked to guess his identity. The winner received a Paramount Record of their choice. The contest entry forms accompanied the record all 10,000 sold out. Staggering when you consider that this was well before the age of mass media or quick communication. Paramount Records hedged their bets by also doing up 7000 promo posters and ads in The Chicago Defender, the premier paper for the other side of segregated America.

The initial pressing quickly sold out creating the market for a second pressing, a then rarity for such a specialized market.

Interestingly enough, Charlie had recorded (briefly) some religious hymns under the pseudonym J.J Hadley. Either name was an accepted answer for the contest.

Charlie was of average height and slight build (135lbs) but some of his material was musical boasts concerning his prowess and potency. (Charlie as a proto rapper?). Mostly though, he and other blues forefathers would recite topical verse over often simple but hypnotic beats. Charlie is believed to be the first one to use the now standard twelve bar blues pattern.

Initially, before the lexicon of blues standards was born, the tales in Charlie and his peers songs were intricate, image rich American gothic. Flannery O’Connor meets the juke joint.

In Charlie’s lyrics, depending upon your point of view, God or the devil was ever present, not as an incarnation, but as natural calamities. Floods, the taste of one’s mortality, even boweevils. Despite the commercial considerations of what Charlie recorded, there was always more than just some woman having done him wrong. Deeper themes whose narrative complexity still retain their power in this modern age when Charlie’s way of life has long since vanished.

Another key appeal of Charlie’s work was his vocals. The lyrics were often obscured. The cadence of his voice being used as a second instrument. There is something about the sound of those simple, yet hypnotic beats mixing with that voice. It reaches deep down into you, a primal twitch. I like to listen to this in the dark. You should listen to this in the dark, listen anywhere desolation and appetite can be poetry.

It was said that Charlie had, had eight wives. At the very least he had eight roommates. With a hair trigger temper he had fought with all of them.

When not in jail, sick or recording, this American troubadour was out living the life he would represent in his art. Reporting on what he saw and interjecting his own opinions. One of the strongest tracks off of CD #2 is “High Water Everywhere”. This was based off of the 1927 Mississippi flood and its after effects as he witnessed them. It is from the episodic growl as much as the cabaret theater world of Brecht/Weil that Tom Waits would build his initial musical foundation off of.

Long time brother in arms Willie Brown spent years observing and playing with Charlie. From the practical application of this apprenticeship Willie became a great bluesman in his own right. It was from Willie in the 1920’s a teenage Robert Johnson attempted to learn.

With the onslaught of the depression, many small record labels folded, times were tough all around and Charlie made due the best he could. By the mid 1930’s, Charlie, in his mid forties began to feel the effects of his lifestyle. A fight one night ended with Charlie having his throat slit and living to sing about it. Bad woman, good cocaine and strong whiskey with an endless supply of cigarettes to mark the time in between each.

1934 saw the depression finally beginning to bottom out. People no longer needed to be tunnel-visioned on how to eat, where to find work. It would be several more years until it was done with completely. The theory that affordable distractions will always make money in times of trouble has been proven again and again.

W.R Calaway of The American Record Corporation wanted to record Charlie. For what would be Charlie’s last sessions he tracked the artist and his wife Bertha Lee who would share vocal duties, down to a Mississippi jail where they were both serving time for having had one of their knock down drag outs at a house party. W.R Calaway made bail and brought the pair to New York.

New York was having one of its bad winters. Charlie was already frail and sick. Both in lyrical content and in his haunted performance Charlie seems to have felt the ebb and flow of his mortality.

One of Charlie’s last recorded songs was 34 Blues, 34 being slang for “go away”. Three months after his final sessions while living on a plantation with another woman Charlie died of a heart condition brought on by an attack of rheumatic fever. As he lay dying, in delirium, it was to the reciting of one of the religious hymns he recorded as J.J Hadley he occupied his last days until death finally took him.

The sound on these three CDs is good, it has been cleaned up, but not sanitized to the point of loosing its soul in studio artificiality. At times there is the ambient presence of a 78’s hiss. It works, it belongs. The effect is akin to listening to some of the great prewar Edith Piaf recordings which contain the same hiss. It furthers the effect of being spoken to from another time, without ever distracting or lessening the art. So well does it work, it almost seems as if these two artists, so different, both incorporate the hiss and technological limitations into their deliveries and technique.

The songs are all presented in chronological order which I always think is a nice touch. Aside from the aforementioned “High Water Everywhere” another personal favorite (CD #2) is “Mean Black Moan” which features a trance inducing guitar pattern, with the singing violin sounding almost like an upper register clarinet all occurring while the tale is told.

Henry Sims on violin is perfect. He had a touch which managed to be both raw and subtle. He would go on to work with later day bluesman Muddy Waters. It offers a glimpse of what might have been if Charlie had had opportunity for more instrumentation or at least further sympathetic accompaniment.

The packaging is nice. The three CDs are packaged in hard cardboard sleeves to look like old 78’s which are housed in a good looking little box with an eighteen page informative booklet.

This compares nicely with “The Best of Charlie Patton” (1 CD Yazoo). Yazoo was one of foremost revivalist of early American music chroniclers. This is one CD and not really that much less than this three CD set.

The crown jewel for any serious collector is “Screamin and Hollerin the Blues:The Worlds of Charley Patton” (7 CDs Revenant Records) This is literally functional art. Designed to look like a large 78’s record box, it includes lots of reading material including the long out of print thesis on Charlie by John Fahey, stickers interviews and other Charlie related literature. An investment to be sure, but worth it.

It was not until 1980 Charlie was actually induced into The Blues Foundation’s hall of fame. In 1990 singer John Fogerty paid for a proper funerary monument to be erected. Other Mississippi bluesmen are talked about and sited more often. Charlie’s stuff, because of its deeply personal delivery would be far harder to emulate. This is the king. From the roots of this musical tree would flow far reaching and diverse branches.

-Maxwell Chandler-

![]()

Kenny Dorham - Afro Cuban Blue Note

Kenny Dorham-trumpet

J.J Johnson-trombone

Hank Mobley-tenor Sax

Cecil Payne-baritone sax

Horace Silver-piano

Oscar Pettiford-bass

Percy Heath-bass

Carlos “potato” Valdes-conga

Art Blakey-drums

Kenny Dorham was as talented as his peers, holding his own against the original wave of bop innovators whom he played alongside night after night and then going on to add his voice to that of the subsequent generation of young lions, who expanded upon those first theories. He maintained a presence among the next generation of musician/artists, working on various ideas in tandem, creating en-mass a body of work which is still as exciting and important today as when it was first conceived.

Kenny Dorham had his first steady gig in 1944 after leaving the army where he was also a prize fighter of reputation, in Russell Jacquet’s band. After serving time in several big bands including Lionel Hampton’s, he began to play with the smaller bop ensembles. He had begun to have his playing noticed with such early appearances as on Billy Eckstine’s Mister B and The Boys (1946 Savoy). This initial notice allowed him to cut his teeth in early small ensembles of Bird and Bud Powell. Most notably during this time, he replaced Miles Davis in one of Bird’s combos for several years.

Throughout his career Kenny Dorham liked to surround himself with familiar musicians, ones with whom he felt a rapport. The drummer Max Roach shared the band stand with him under Charlie Parker’s leadership for the Royal Roost Sessions (1948 Savoy). Over the space of various record labels and several decades he and Max would team up, including a time when Kenny would replace, the then recently deceased, Clifford Brown in the Brown/Roach combo.

During the giddy hey day of early bop, Kenny had been overshadowed by Fats Navarro. Ensuing years have seen somewhat, a reversal of fortune. There is no “Fats” school of playing, but aspects of Kenny’s technique are still fueling young horn players.

While time has not completely opaqued his name and contributions in the same way as that of fellow trumpeter Fats Navarro, Kenny Dorham has not fully received his due. Part of the problem lay in the fact that some of his best work was produced as a “sideman” on other people’s dates. Kenny Dorham did create some now classic albums under his own name, and even as a sideman, but he never had a steady, long term group of his own with which to build an audience off of. Regardless of a lack of a permanent group, he did often appear with the same roster of artists, only the date’s “leader” being a variance.

The other main handicap to his ascension was that, even though he did tour and travel early in his career while part of big bands and early bop-bands, his was never a jazz evangical mission in the same sense as Miles Davis. Gaining exposure and name recognition through extensive touring. Most of his jazz life was spent in New York with the occasional foray to the West Coast.

Kenny Dorham had two distinct “golden” periods. The 1950’s saw him playing complex hard-bop with its main architects. This first phase is where Afro Cuban is from.

In the forties Art Blakey had originally created two earlier, more big band-ish versions of the Jazz Messengers, a septet and a seventeen piece band. A decade later, he revived the name, with a harder driving sound and the idea of making it more of a “jazz collective”.

Pianist Horace Silver had been backing sax player Stan Getz, Lester Young and Miles Davis. Drummer Art Blakey had been on some of the same dates and recruited him for the immortal two live discs Night at Birdland Volumes 1 & 2 (1954 Blue Note) which also featured Lou Donaldson and Clifford Brown. This was the birth of hard-bop. A genre which built off of bop but presented new rhythmic and sonic possibilities. This was also the appearance of the first, short lived new incarnation of The Jazz Messengers. The group was a collective in as much, they all shared writing chores and who ever found employment is the name which would be showcased before “and the Jazz Messengers”.

The “second” incarnation of the group featured Hank Mobley on tenor sax and Kenny Dorham on trumpet. Between the two line ups of the group there was a year of “Jazz Messenger” inactivity during which none of the artists remained silent. Horace Silver was doing a residency at Minton’s Playhouse as a result of his appearance on the first 50’s Jazz Messenger discs. Those records opened up new sonic considerations for him and he enlisted tenor sax player Hank Mobley to continue down the path he started a year earlier. The second version of The Jazz Messengers appeared on “Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers” in full. During this time they recorded Hank Mobley’s first solo album Messages (Blue Note) minus Kenny, Donald Byrd’s Transition (Blue Note) and Bird’s Eye View also minus Kenny and Kenny’s own Afro Cuban. Afro Cuban added trombonist J.J Johnson and baritone sax, conga to the line up. Much like their immediate Messenger predecessors, there would be two live discs, Live at the Bohemia (Blue Note) which capture the band at their best. They went on to record an album for Columbia.

Unfortunately it was felt by the rest of the band that Art Blakey had short changed them when pay day came. A mass musician migration ensued. Horace Silver would now mainly lead his own ensemble of which Hank Mobley was an early charter member. Horace would maganimously allow Art Blakey to keep the Jazz Messenger moniker. To capitalize on the Jazz Messenger popularity, the various ex-members would all start groups with similar names, Kenny leading The Jazz Prophets. Despite the talent of all involved, these groups were all short lived. Horace Silver having the most success in band longevity a few years later with the Junior Cook/Blue Mitchell version of his group.

Afro Cuban is a compelling album. It is not straight out hard-bop. The ensemble is slightly larger than what would become the standard hard-bop de-rigor trumpet and sax front line. It is not merely big band either. The combination of jazz drum kit with the added percussionist give all the songs a groove that is noticeable but never appears overly urgent. Throughout the album there is a tropical feel but not all the horns try to play only in a Latinized manner.

J.J Johnson had experimented with tropical beats on his own album The Eminent J.J Johnson Volume 2 (Blue Note), which featured Hank Mobley and Sabu Martinez on conga. His tone, as always is clean, clear allowing for greater appreciation of what he plays, as opposed to the slurred lines often employed by trombonists before J.J.

This is early Hank Mobley and although there are no weak links on this album, he truly shines. His tone at this point has the warm round sound. Fully showing his Lester Young influence while not sounding as laconic or fragile.

Art Blakey is important to jazz, if for no other reason, than for all the greats who passed through his band over the years. With few exceptions, the list includes jazz’s “who’s who”. Those who were not directly a Jazz Messenger usually had at least one Messenger in their band. While I think Art Blakey is a good drummer and I own many Jazz Messenger records, I am not a big fan of his playing in itself. My main issue is I sometimes find his rolling thunder approach distracting from both the piece and other players. Here though, is found a more sedate and nuanced Art Blakey than is to be heard on other dates.

Horace Silver is found here in his usual funky-percussive best. In all his albums he would never deviate too far from his established hard-bop way of playing or composing, but it is all good. He is one of the greats.

All the pieces on the album were written by Kenny except one, Basheer’s Dream, which was written by Jazztett member Gigi Gryce. This song features the baritone sax stating the melody, then the rest of the group enters. It is refreshing to hear the baritone played with a little more fire than is wont to be found on the cool West Coast style music that usually utilized baritone. Like all the other pieces on the album it has an infectious groove.

One of my other favorite tracks is Afrodisia. It seamlessly mixes a Latin groove with hard-bop sounding solos. When the trumpet solo ends and the sax solo starts, if you listen you will hear the rhythm shift tempos several times before the trombone takes over. Simple, yet dramatic.

Lotus Flower is a tropical ballad which manages to conjure up both Duke Ellington and the musical form Bolero (style not Ravel piece). Kenny Dorham’s tone switches between a soft whisper and brighter sounding solo statements.

This CD collects what had originally been two 10”Lps. The two sessions were similar in feel and there is no jarring effect in hearing them combined.

Although I highly recommend this CD, a few bones of contention for me: This is just a regular CD, it has not received any special remastering. The sound is not bad, but one can imagine what the Rudy Van Gelder (RVG) version would offer up to the listener. The original liner notes are reproduced with a small addendum concerning the last bonus track’s name, the real one being found after the fact. It would have been nice, considering collectively, the body of work these artists all went on to do, if we got “Another look at…” which are new, added notes found on all the Blue Note RVG series. The CD does include two tracks which do not appear on the LP configuration, but one song has its alternate take right after it as opposed to putting it after the sequence of original album tracks.

The appeal of Kenny Dorham for me is both his tone and writing. He could play soft ballads, but it never came across as an affectation. Kenny could also play hard. What is interesting in his more muscular playing is that unlike all his peers he never went into the showy-piercing upper registers nor did he help sow the seeds of what would become the splatter school. Everybody else could be found in one if not both of these places. Yet Kenny found a third unused way. This unique grace helped earn him the nick-name “Quiet Kenny”.

His writing, from his earliest days was always complex, avoiding all of the quickly established bop and hard-bop formulas. Low paydays made him often have to have day jobs in munitions and medical plants and once at a sugar refinery. He would use his writing skills to ghost write complex charts under the pseudonym “Gill Fuller”.

The sixties found Kenny still artistically evolving. This was his second golden period. Kenny was supportive of the new up and coming younger generation of players. Count Basie famously, was one of the few musicians not directly connected to Miles Davis’s The Birth Of The Cool (Blue Note) to realize how important this “new thing” was. The Count was also aware of Thelonious Monk’s genius well before many others. Coleman Hawkins, one of the holy trinity of the first great tenor sax players (Ben Webster, Lester Young being the other two) employed Thelonious Monk and also recorded an album with young Turk Sonny Rollins(Sonny Meets Hawk RCA/Victor 1963). Unlike these two, Kenny ‘s playing and writing always smoothly integrated well into what was currently going on. Kenny managed to transcend participating in mere musical experiment of two different schools/generations.

His short lived Jazz Prophets had many of Blue Note’s young lions. Herbie Hancock, Kenny Burrell and future Jazz Messenger Bobby Timmins all passed through.

The one person from his short lived group whose career Kenny would have a profound effect on was the young Joe Henderson. Joe was part of the second, great holy trio of tenor sax players (Wayne Shorter and John Coltrane being the other two). Their first recorded partnership was Kenny’s Una Mas (Blue Note) which borrowed the tropical leanings of Afro Cuban, but added an even harder edge. Together they went on to record Joe’s Page One (Blue Note) which featured the song Recorda Me by Joe, written when he was only a teenager and also the now standard Blue Bossa written by Kenny. McCoy Tyner most famously, of the classic John Coltrane Quartet, is in the piano chair.

After these albums Joe and Kenny would do In and Out (Blue Note) which had both Elvin Jones and McCoy Tyner from John Coltrane’s band and the album Our Thing (Blue Note) which was the debut of composer/pianist Andrew Hill.

While nurturing the next wave of jazz greats the sixties found Kenny serving as a consultant for the Harlem Youth Act which was an anti poverty program. He also served as a member of the board for the New York Neophonic Orchestra.

Sadly the end of the decade saw a decline in Kenny’s health. 1972 he died of kidney failure.

While he never wildly altered his artistic mission or style there is a progression which appears throughout his body of work. A subtle evolution, never enough to alienate fans unable to recognize a new style but also managing to avoid churning out cookie cutter albums of formulaic jazz.

What better nod to a man of so generous a spirit than to check out one of his many great albums?

-Maxwell Chandler- March '06

Editor's note: I see Amazon (UK) have a 24-bit remastered version on Toshiba, ASIN: B0002MOMSM

![]()

| Click Here |

Page one of Max's Jazz reviews